How welfare reform changed American poverty, in 9 charts

By Max Ehrenfreund

August 22 at 9:30 AM - The Washington Post

Twenty years ago, President Clinton kept a promise. "I have a plan to end welfare as we know it," he said in a television spot during his campaign for office. He did, on Aug. 22, 1996.

The law that the president signed that day, together with other policies enacted by Congress and the states, profoundly changed the lives of poor Americans. It was intensely controversial at the time — a controversy that is heating up again today. New data on the hardships of poverty in the aftermath of the recent recession have exposed what critics say are shortcomings of welfare reform.

Clinton ended the traditional welfare system, called Aid to Families With Dependent Children, under which very poor Americans were effectively entitled to receive financial support from the federal government. In the new system, known as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, applicants must meet a range of strict requirements that vary by state to get help — working, volunteering, looking for a job or participating in skills training.

Here are nine things we know about how the lives of America's poor have changed.

1.

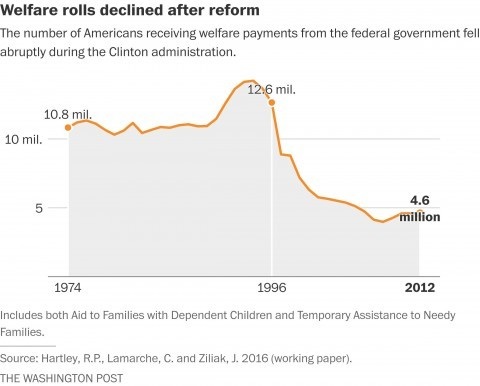

After Clinton signed the reform, Americans left welfare rolls in droves. People receiving federal welfare payments fell by half in four years, to 6.3 million in 2000.

The decline had begun a couple of years previously, as states made changes to their policies ahead of the implementation of the new federal law. The rolls had reached their apex of 14.2 million in 1994.

2. But the government didn't save money

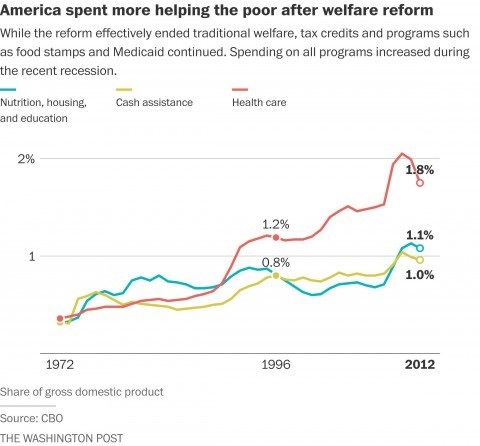

Despite shrinking welfare rolls, the federal government spent more on programs that help the poor.

Part of the reason was that, under the reform, states could redirect

that federal money to programs other than welfare, such as child care,

college scholarships and programs that promote marriage as a way to prevent

poverty.

Tax credits for the poor also maintained overall cash assistance at a stable level, and programs such as food stamps expanded — especially during the recession that began in 2008.

3.

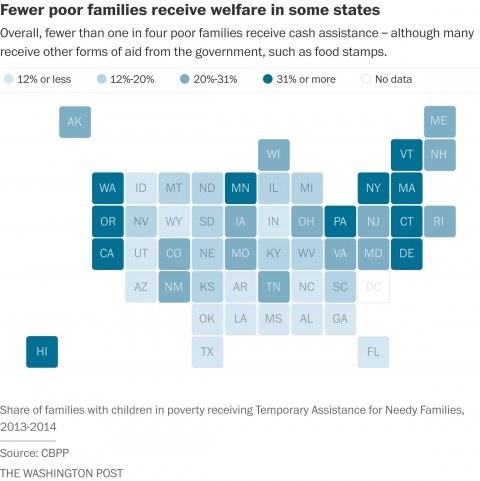

Just 23 percent of all families with children living in poverty receive welfare, according to estimates by the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Only in three states — Hawaii, California and Vermont — is the share more than half. Many of these families, however, receive other kinds of help from the government.

4. Poverty is higher than in 1996

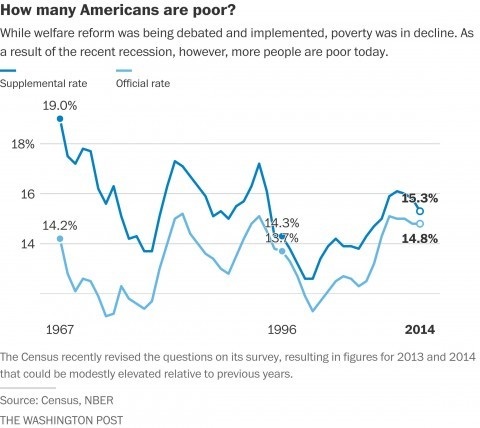

Economists and experts on poverty fiercely debate whether the 1996 law made poor Americans better off.

Various measures of poverty show that the number of poor Americans has fluctuated with the economy. The official measure has vacillated around 14 percent for at least half a century. That measure, however, excludes the value of food, housing and other resources poor families receive from the government. A supplemental measure that takes account of those government programs shows a gradual but unsteady decline in poverty.

Economic conditions were excellent during the debate over the welfare reform bill in the '90s, and poverty was already declining before Clinton signed it. Initially, standards of living for poor Americans continued to improve as the law was being implemented. During the recent recession, though, poverty increased again.

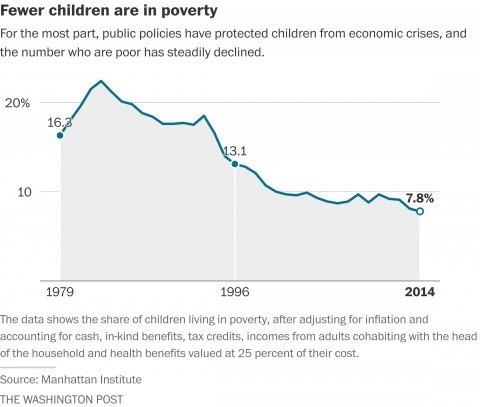

5. Poverty among children has declined

Children, by contrast, have been largely insulated from shifts in economic conditions, and the rate of poverty among children has steadily declined.

Federal policymakers have made reducing poverty among children a priority by offering tax credits to parents and giving kids health insurance and free lunches at school. In recent years, though, the share of children in poverty has not declined as quickly as it had in the past.

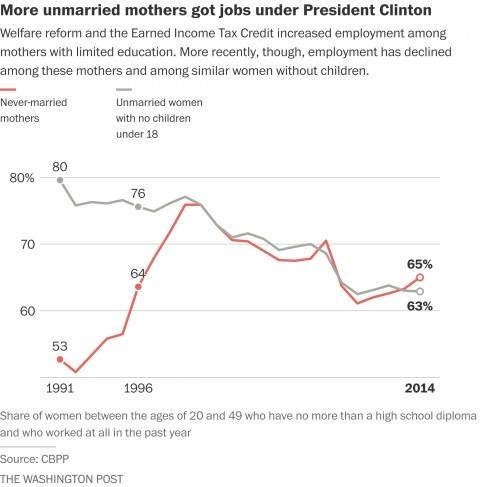

6. More unmarried mothers entered the formal workforce

One particular concern for lawmakers as they debated welfare reform focused on unmarried, poorly educated mothers, who made up a large fraction of people on the rolls in the old system. Many worried that these women would be unable to find work because they had to care for their children.

In fact, according to research by Kathryn Edin and Laura Lein, it is likely that many of these women were already working — under the table, to avoid losing their benefits under the old system. In any case, many of them entered the formal labor force after the reform.

While their numbers had already been rising, the share of never-married mothers with no more than a high school diploma who were working in the formal sector jumped from 64 percent in 1996 to 76 percent in 2000, matching the same as the figure for similarly educated women without children.

Proponents of reform argue that the restrictions Clinton enacted encouraged many people to work and end their dependency on help from the government. At the same time, the robust economy might have drawn more workers into the labor force, and the expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit — a bonus for poor workers that rewards them financially for working and earning more — provided another reason for people to find jobs.

More recently, though, employment has declined for these mothers — as it has for similar women without children and for people with less education in general.

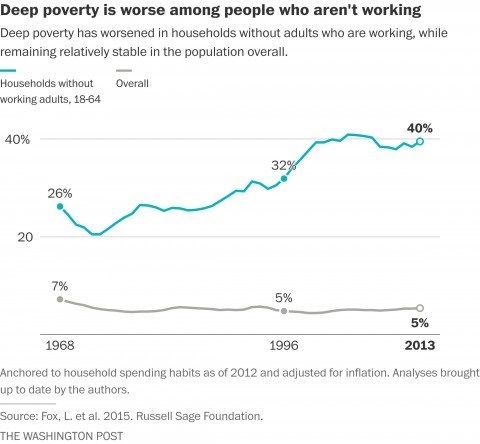

7. Deep poverty increased among families with unemployed adults

Meanwhile, there were a few parents who never were able to find work. Critics of welfare reform say the law put these people and their families in dire straits. If they could not satisfy the law's new requirements for employment or training, they could no longer receive welfare payments from the government. If they did not have a job, the Earned Income Tax Credit would not help them either.

The rate of deep poverty — defined as the share living on a household income less than half of the official poverty level — increased among this group following reform, from 32 percent in 1996 to 39 percent in 2000.

Whether this increase was a result of the reform or broader trends in the economy is unclear, since deep poverty among households without working adults had been increasing for some time before Clinton signed the legislation. The figure remains around 40 percent today.

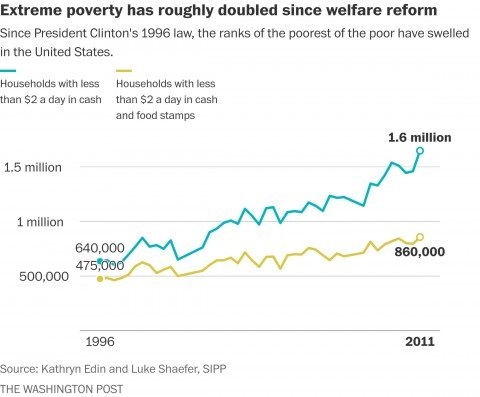

8. Millions of people live on less than $2 a day in formal income

In the worst case, some of these families might be getting by almost entirely without cash. Edin and her colleague Luke Shaefer published a book last year presenting evidence that the number of households living on less than $2 a day per person in cash — what they call "extreme poverty" — has roughly doubled since the reform. (Many of these households are receiving help from the government in forms other than cash, such as health insurance and food stamps.)

Conservative scholars have criticized Edin and Shaefer's work.

In a paper published Monday, Scott Winship of the Manhattan Institute argues that the data could reflect an increasing reluctance among the poor to report their income to federal interviewers, rather than an actual increase in poverty. He points out the data show an increase in the number of extremely poor people among groups unaffected by welfare reform, such as households without children.

"Essentially no one is living under $2 a day," Winship said.

He argues that welfare reform was an important accomplishment that ended many families' dependence on public assistance and encouraged them to provide for themselves.

Edin acknowledges that many people are likely concealing informal sources of income from surveyors, but she points out that methods the extremely poor have for getting cash are not helping them escape poverty — and can even be dangerous.

If parents "are selling plasma and selling sex and picking up tin cans for a dollar an hour, the question is, is this what we want parents of children to be doing?" she said. "Wouldnft we rather have them going to community college?"

9.

These days, among very poor, unmarried mothers, welfare is far less important to the average family budget. Instead, these households rely more on food stamps and disability than in the past. For these families, earnings in the labor market remain scant and have even decreased in recent years. The are getting less from the government overall, and the data suggests they have not been able to make up that money by fending for themselves.